“Why I Like Eren Jaeger.” That’s the title of a post I wrote 10 years ago.

A lot of things sure have happened since then.

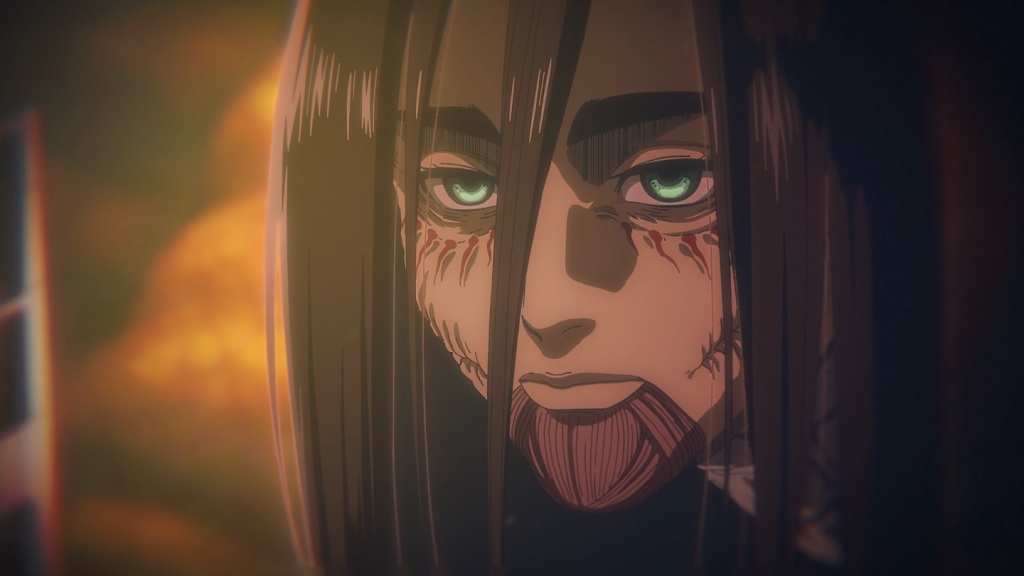

The anime Attack on Titan recently concluded after what seemed like an eternity, and we the viewers have been left to interpret Eren in his entirety, from the hotheaded protagonist he was at the beginning to the apocalyptic villain he becomes by the end. Given all that has transpired, not least of which includes mass genocide, can I still say that I “like” Eren?

WARNING: SPOILERS OF THE END OF ATTACK ON TITAN AHEAD

Obviously, I can’t condone genocide no matter how it might have come from a place of wanting to protect his friends, or even if the alternative was a different form of genocide. But the reasons I was fond of Eren as a character ten years ago had little to do with anything like moral and ethical values or good decision-making. Instead, it was because he’s a deeply flawed character with some genuinely positive traits—namely his ability to motivate others through the sheer force of his ceaseless drive to press ahead.

In 2013, this is what I had to say:

I see Eren as the kind of guy who makes people better than him feel worse for not accomplishing as much…. This is mainly what drives his relationship with Jean, as Jean is clearly smarter, wiser, and comparable in physical ability to Eren, but lacks his ability to throw himself into danger. On the other hand, Eren’s narrow-mindedness is the reason he can’t accomplish everything on his own, and…if he were a leader of men…he would probably send them all to their deaths just by being himself….

The result is that the Scout Regiment (or Survey Corps), a group infamous for being full of eccentrics with death wishes, gains and benefits from one of the most rational and reasonable individuals. At the same time, it means Eren has always been someone who needs others to keep him from being a living train wreck.

This is not a defense of Eren but an understanding of his relationships and the effects he has on people who are better than him. He inspires others to do what they thought impossible or inconceivable. Nowhere is this more relevant than with his closest friends, Armin and Mikasa. He pushes them to achieve greater heights through the example of his will, and this remains true even as Eren turns them against himself.

Eren, Mikasa, and Armin are parts of a whole, and it’s a relationship that persists even in opposition. I think that Eren purposely pushes his friends away because he knows they have what it takes to stop him. Similar to Dr. Manhattan in Watchmen, Eren becomes able to move in four dimensions, and this ironically makes him unable to challenge fate. But Mikasa and Armin are not beholden to such cursed omniscience, and they ultimately defeat him and help remove the titan ability from the entire world.

Mikasa killing Eren is not only one of the most powerful scenes of the finale, but a key moment in the series as a whole. The presence of titans in their world for 2000 years is because Ymir, the Founding Titan, is trapped by her undying and contradictory love for King Fritz, her longtime master and abuser. Despite knowing how much Fritz saw Ymir as nothing more than property, her feelings keep her loyal out of a desperate need for human connection. Seeing Mikasa behead the love of her life for the sake of the world shows Ymir that it’s possible to break the mental and emotional chains binding her. And all of it comes back to what made Mikasa fall for Eren in the first place, back when they were children: When others would have said to run, Eren implored her to fight. He pushes others to not give up, even if it means he himself becomes the enemy.

So the answer is yes: I still like Eren Jaeger for the mess that he is. I can’t support the consequences of his actions, but the story of Attack on Titan is very much about the ugliness of humanity, and in many ways, Eren exhibits some of its worst qualities. However, much like how there are glimmers of hope that flicker in and out amid despair, he casts a light on others and gives them power, however great or small, to do more—even as he himself is subsumed by darkness. Ultimately, he ends up being a unique protagonist turned antagonist, a child given far too much responsibility and burden, a cautionary tale of why you don’t have to automatically cheer for someone just because they’re the main hero, and a figure remarkably complex because of his profound limitations.