In the past few years, I’ve developed a terrible interest in reading and viewing arguments about martial arts, from kung fu to MMA and beyond. There’s a combination of established knowledge, lost knowledge, myths and legends, fraudsters, hero worship, dick-waving, differing philosophies, and genuine curiosity that makes it a weirdly compelling shit soup. During these trawls, I occasionally see an argument that goes something like “If their kung fu is so great, why don’t they prove it in the ring, and also make a ton of money?”

But what I was surprised to find is a response of sorts to that question in the pages of the manga Mashle—a series that asks, “What if Harry Potter was a non-magical himbo who overcame all obstacles through comically absurd physical prowess like Saitama from One Punch Man?” Not only does Mashle do a surprisingly good job of addressing the inequality inherent in its world, but it also cuts through expectations in other ways too, including how and why people learn to fight.

It’s important to note that con artists are a dime a dozen in the world of martial arts. It’s the realm of claims of supposed no-touch knockouts, poison fists, and chi energy. Even when you put such ridiculous “feats” aside, there are plenty of generic schools that are justifiably derided as “McDojos” or “belt factories,” essentially teaching nothing of substance. Because of this, many have reasonably become skeptical towards anyone who purports to fight with superhuman abilities. Asking for real proof makes sense, but ut there’s this peculiar jump in logic I see sometimes, where “prove it in the ring“ becomes “doesn’t everyone want to prove themselves?”

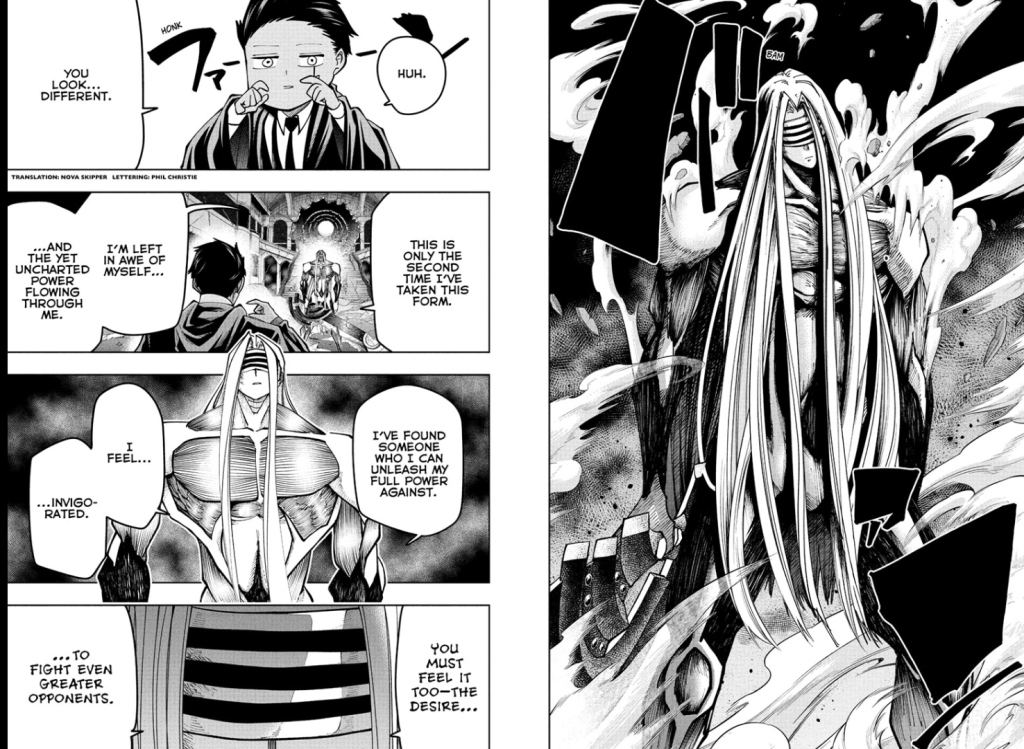

That’s where Mashle and its hero, Mash Burnedead, come in. During one of Mash’s most fearsome battles to date, his opponent says, “I’ve found someone who I can unleash my full powers against. I feel…invigorated. You must feel it too—the desire to fight even greater opponents.”

To which Mash responds, “Not really. I don’t want to fight stronger people. I don’t find it exciting at all. I still…just want to go home.”

This whole scene is a brief gag in a larger action scene, but Mash’s answer is a succinct counterpoint to the notion that everyone who truly learns how to fight has this killer instinct they need to unleash upon the world, whether for profit, fame, or to prove something. It actually takes a particular kind of person to want to willingly get in harm‘s way in order to show the world what they’re capable of.

One of the martial arts videos I‘ve watched (see above) is from an instructor on Youtube named Adam Chan, about the Hakka fist. As Adam explains, the Hakka are an ethnic group in China who were historically very poor and had to migrate a lot, and the various martial arts they developed came from civilians needing to survive against prejudice and xenophobia rather than as part of an army or in order to engage in duels. This is where Mash is: he didn‘t learn how to fight because of ego, bravado, a thirst for more, or because of a chip on his shoulder. He did it to protect himself and those dear to him.

Within online discussions of martial arts and fighting, conversations end up getting geared towards “Whose kung fu is strongest?” in the literal sense. But Mash Burnedead represents the reminder that sometimes it’s the wrong question to ask. The desire to hurt others and risk getting yourself hurt in the process is not the only way to view things, even if there is a certain glamor to the idea of honing oneself into a human weapon.