Madrugada, the latest record of MJ Cole, reveals an entirely different side of the British artist born Matthew Coleman. By shunning dance music, where Coleman has made his name since the late ‘90s, it places the piano front and centre, recorded in the luscious surroundings of his London studio in the summer days of 2019. The sounds of his Yamaha U1 are processed heavily, but this is an analog album with both its feet in the classical realm. Instead of analog synthesizers and heavy samples, Coleman had at his disposal a 14-piece orchestra, on call to realise the subtleties of a vision that he’d harboured since he began learning piano through adolescence. “I’ve made hundreds of records and had albums out before, but this record has always been brewing in the background,” Coleman says.

Before he became one of UK garage’s first true stars, Coleman was a rising classical musician inspired by his father, who would sing and play piano at home. He found garage through his work with drum & bass label SOUR, where he worked as a tape operator and sound engineer, and from here his rise was meteoric. The catalyst was “Sincere,” a debut single that merged the UK underground with the mainstream, becoming one of the first garage records to break into the top 40 Singles Chart. The stage was set, and Coleman has fulfilled his early promise with a catalog of productions and remixes that have shaped the UK garage sound and introduced it to a global audience. During the genre’s heyday, Coleman remixed Amy Winehouse, appeared on Top of the Pops, and was nominated for the Mercury Prize.

Yet if you listen carefully, the fingerprints of a classical upbringing can be found through all Coleman’s work—the subtle piano and the rich, emotive harmonies. But the requirements of dance music, that it makes people move, have always required that he demote his classical instincts, prioritising functionality over feeling. On Madrugada, he switches this up, delivering a contemplative long-player that sits closer to the work of Nils Frahm and Ryuichi Sakamoto than his electronic peers. To learn more about it, EDMjunkies visited Coleman in his new Shoreditch studio, where he discussed his recording processes and musical visions. Here is an edited version of that conversation.

Madrugada was your first album in these classical aesthetics, distanced from the garage people know you for. How are you feeling about the release?

I’m feeling good. It’s not really a change of direction because this sort of music is something that has been brewing all throughout my career. I am still making pop and garage records, but this was a golden opportunity to realise my inspirations from the past. You have to remember that I grew up in classical music, and I’ve been classically trained; I started to play the piano when I was five. Some of my listeners might think this isn’t the usual stuff he makes, but actually garage came after this stuff. It has been lovely to play the piano freely; to work with big string ensembles, and to get really involved in the classical side.

Where did the album begin?

It all began when I went into Decca to speak to them, initially about doing some dance remixes of some of their classical repertoire. I wasn’t keen on that because I come from classical and I thought that dance reworks of classical things were a bit naff, but we got talking and I told them I’d love to do a piano album with strings. They said, “Ok, Cool.” I received an album deal in half an hour! That’s really how this all started.

Was it scary to have such a blank canvas?

Not really, and I certainly wasn’t lacking inspiration. I’ve actually been recording voice notes for piano improvisations since voice notes started basically, because I’ve always wanted to do a piano album. I already knew what I wanted to do. So when it was all agreed, I began looking in two places: I went back to those piano improvisations and began to work them up, and I also took a more traditional MJ Cole stance in that I went to Splice, where you get the royalty-free samples, and downloaded loads of string samples. And I began playing around with these samples, in the same way I would with a remix, and they became the basis for some of the tracks on the records. The record’s foundations were either piano improvisations or sample wizardry.

How do you think the album will be received among your fans?

I guess people who don’t know my music that well, who just think I am a garage DJ, might be more surprised than people who know me a bit better, but there’s been hints of this through all my records. My love of strings has always been there, and I’ve always used a lot of piano. I actually don’t think that people who know me well will be too surprised. I think they’ll probably welcome it in that it’s an opportunity to show that side completely by itself, without any need for it to be a radio thing, or a hook, a chorus; without the traditional constraints of contemporary dance music.

So you began by looking for string samples on Splice. What exactly were you looking for?

Just something that pricked my ears. Quite often the way I get ideas to make records, the beginnings of music, they come from tiny little cells, or fragments; really I am just looking for something to light the touch paper. So I just used my ears to pick out interesting sounds and then, pretty much like a remix, I spread them out over the keyboard in a sampler and then started playing really with my fingers, finding interesting cells. I then built around those as a harmonic base.

It’s important to say that I didn’t use string samples at all in the final album. I just chopped them up. I then played real strings over them, and then in the end the real samples went away, and I played piano over the top. The final piece was having 14-piece strings recorded over the top.

“Still now, if I get stuck with any record, I’ll bounce the whole thing as stems then start again completely, and make a whole new palette of sounds and approach it from a different perspective. The remix mentality of my early years is something I resort to regularly.“

—MJ Cole

It’s an interesting way of working. How does this compare to your earlier records?

This approach is actually fairly similar to when I was working from my bedroom as a teenager. Back then, I had a sampler and I’d just get little bits of sounds and they’d inspire me to make full records. Nowadays, my records start with the piano and have piano all the way through, and they’re more traditional, but those early days will always be part of my DNA. It’s part of my toolbox to warp and twist things and shine a different light on stuff. Still now, if I get stuck with any record, I’ll bounce the whole thing as stems then start again completely, and make a whole new palette of sounds and approach it from a different perspective. The remix mentality of my early years is something I resort to regularly.

You also mentioned that piano improvisations formed the basis for some tracks. How did those tracks begin and evolve?

Well, it’s hard to say where these improvisations come from, but improvisation is something I enjoy doing. I think after playing for so many years your fingers find familiar patterns. Often I’ll start playing the piano when the television is on, and I’ll pick something interesting out; from there, I’ll go off in a completely different direction. It’s all about finding springboards and starting points. Once the ball is rolling, then I’m off. If I’m away from the piano, I’ll record these melodies as a voice note and then go back to the piano and try to find the headspace I was in, and then start actually recording.

What piano were you using?

It’s a Yamaha U1, but I also used a Celesta pedal, which you push in the middle. It puts a layer of felt, like an actual layer of material felt, between the hammer and the string to make it quieter, but it has the effect of making the piano feel softer. My Yamaha, without that pedal down, is actually hard, and very poppy. So this whole album had the pedal down.

Where did you buy the piano from?

I hired it from a place called Piano Warehouse. I hired it for a year and then I loved it so much that I bought it from them after that. Every piano has its own character, and it can be the same model from the same year from the same factory, and they all have a different character and different feel. I know immediately when I touch a piano if I am going to get along with it. I suppose it’s like a snooker player with their cue, or a barber with their special scissors. So when I go to pick a piano, I would never just order it and have it delivered. I need to go and play as many pianos as I can and see if they speak to me.

How did you go about recording and processing these organic sounds?

The piano was recorded through the Josephson C42’s running through a Tubetech MP1A preamp. I used some DPA mics underneath the keyboard for some tracks with Neve preamps. The [Celeste] pedal was down throughout the recording, and the strings were sketched out using mostly Spitfire Solo Strings with a Pallette controller for expression and dynamics. Aside from the piano and the strings, pretty much everything else on the record is the result of processing: manipulating recorded sounds with delays, reverbs, choruses, etc., and reversing, pitching, and distorting the results. These were sampled again and laid out across the keyboard to provide a new palette of sounds. Oh yes, and an 808 bass patch.

So the album is heavily processed...

Certainly. I wanted it to be a record that wasn’t just let’s sit down in a concert hall with a conductor, but instead with my MJ Cole twist. I wanted the whole record to be a little bit away from the norm.

Some of the tracks have recordings of what sounds like the mechanics of the piano itself and potentially foreign objects—did you use any prepared piano techniques when recording?

I wouldn’t say prepared piano because that’s when you fiddle with the actual piano itself. The sound on the album is basically an upright piano with all the covers off, so it’s completely naked, and it’s very closely mic’d. I mic’d close to where the hammer touched the strings so you hear the mechanics of the piano, and my fingernails and my sniffs. There is one track on there, “Knocking,” where every sound, except for the 808 in bass, has come from the piano. The actual knocking is my knuckles on the wood.

Where did you do the recording of the orchestras?

We did it at RAK Recording Studio in St. John’s Wood. We did 14-piece strings in there, and then I overdubbed some double bass on some of the tracks. A bassist called Ben Hazelton did that. I’d sort of played the double jazz on keyboard and then he came in after the strings had been recorded and overdubbed the double bass parts.

You recorded the bulk of album in Clerkenwell, in your own studio. How did you find it?

Yep, I recorded the album in the Gin Factory, which I founded with Kate Young in late 2012, but I’ve since moved out here to Shoreditch. I need to be able to work at different times of the day and not disturb anyone else. I am also a sucker for daylight. I’ve spent a lot of time underground, making music without windows, and so anywhere I go now must have a window.

You told me earlier that you maintain a “malleable” system, in that you can work from anywhere. Can you explain this to me?‘

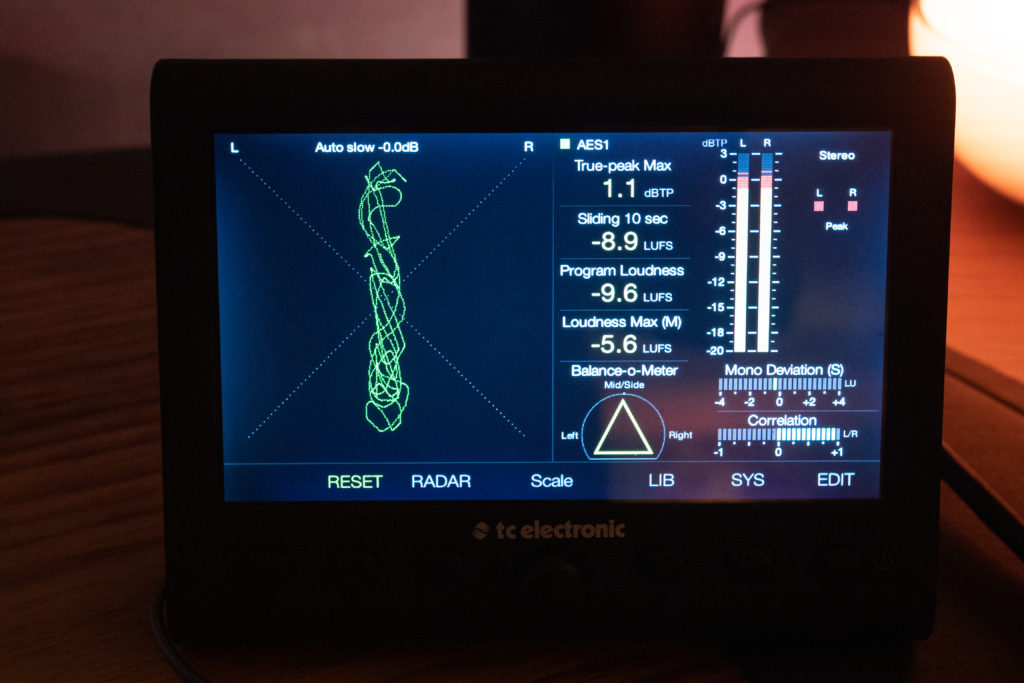

My studio is set up in a way that helps me to get ideas down quickly. I have a set of ATC SCM25 speakers, an array of mics, and some outboard which has been collected over the years, like a like a Prophet 5 and a Teenage Engineering OP1. And my Yamaha U1 piano is always with me; it’s my right hand man. I work from a laptop which slots into my setup and connects with all my interfaces, synths, screens, drives, and outboard. The beauty is that this laptop can be connected to my home setup or any other setup around the world and any session will play perfectly. It’s incredibly versatile. In terms of getting ideas down and beginning pieces of music, my setup can be anywhere really. If I need to do some more detailed listening or use my recording space I’ll go to my studio because it’s fully treated for sound.

You also have a home studio setup. How does this compare?

It’s very simple. Besides the laptop, there’s the controller keyboard, a soundcard, and two speakers. I have a Fender Rhodes in there too. And then there’s a big piano downstairs also, the same one that’s recorded all across the record.

Click to enter gallery

You’ve called the album Madrugada, which translates to the period between midnight and sunrise. Is that because you produced it during the early hours?

No, we chose that title because this period [between midnight and when the sun comes up] has been significant in my life for different reasons. When I was younger, I wouldn’t really start in the studio until 9pm and then I’d leave around six in the morning. So all my early records were made at night. Over the past six or seven years, since I’ve had a family, I’ve become more of a morning person. I ride bikes a lot, so I am up before the sun comes up and I’ve seen a lot of London from that particular perspective. A lot of this album was produced during the day, but I had the setup at home also. Quite often, when my family was asleep, I crept upstairs and vibed out in the same way as when I was making garage records in 1998.

Do you find it easier to access the emotion during the still of night?

Yes, but I think I’ve found ways to get myself into the zone. There’s something about the tranquility of night that helps me. I know that nobody is going to ring me and that nobody needs anything. It feels like the world is standing still and there’s space to explore ideas.

From what you’ve told me, the album-making process sounded like an intense period.

Yes, it was an extremely intense period for me, but in a great way. When you’re making a record like this, you’re making it 24/7 really. I am making voice notes the whole time, coming home, and getting my laptop out to listen to ideas, and then making notes. I was making it all around the clock for nearly four months.

You spoke about the importance of cycling. What role did it play on the album?

Cycling is a meditative experience for me. It’s not like I stop on my bike and have a melodic idea, but when I’m out cycling I am nowhere near a computer or a keyboard, and quite often when I get back home what I’ve been working on that day clicks into place. It’s an important part of my process and without it I wouldn’t be the same person.

So even when you’re not in the studio, your subconscious is working on the material.

It’s totally true. I am a big believer in the four stages of creativity: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification, and a lot of that illumination goes on when your brain is sorting out the material you’ve given it. This is when you’re sleeping, or for me when I’m cycling. You have to be aware as a creative that sometimes you have to just let things boil on the stove for a little while; to let them simmer and gestate.

Can you identify a specific breakthrough that came through cycling?

I think the track “Cathedral.” That came from nowhere. It wasn’t piano improvisation or anything. It was just a day in the studio in Clerkenwell, and it just popped out. I had been on a bike ride near St. Albans cathedral on that day and that’s why I called it “Cathedral.” I think it was almost certainly inspired by that.

How conscious are you during the writing process?

When I am making music, I try not to stop myself at all. I have to sketch and just let it pour out, even if it’s shit. I think it’s important to not hold yourself back; to keep your creative, rather than your analytical mind, going. Quite often you have to make a few rubbish things for the good thing to come out, so it’s important that I don’t stop and think too much. Instead of spending all day trying to do one bassline, I’ll do 12, and just choose the best one. For me, that’s the best way of keeping it all following. The music has to come from somewhere and sometimes you have to go on a funny route to get there.

Do you have any techniques to stop yourself from overthinking?

When I am playing piano, my analytical mind naturally switches off and I go into a meditative state. It’s subconscious, and so sitting there stops me from thinking too much. The analytical part of music also bores me; I’m musically trained but rarely do I think about theory, or what other people will think. I’m always judging my work on how it makes me feel. However, I do become analytical towards the end of a track, but that’s only the finishing stage. And that’s very distinct from the creation.

How do you deal with frustration, when it’s not working?

For me, it’s all about maintaining the flow. I’ve had difficult times, like all musicians. I have days where I think everything I’ve ever done is complete rubbish, and I’ll think the thing I’ve done the day before is terrible. I will be really down, like I’ve lost my allure, but then within half an hour I might sit at my piano or come up with a beat, and suddenly I’ll be back on it. You need a bit of experience to trust, and to believe in yourself, and this helps you to keep it all flowing.

It sounds like you’re a sensitive person.

I’d agree. I am sometimes too sensitive for my own good. Sensitive is a better word than emotional. I am good at expressing emotion through my music, and I am very sensitive as a human. I can annoy myself with how sensitive I am, but I’ve also recognised that this is probably the reason why I make the music that I do.

It’s interesting that you mention that, because the emotion is something striking about your music.

Yes, my fortés are definitely among the harmonic, melodic, musical side. But that’s subconscious for me; it all comes from trying to make sounds that I believe to be true. Other than that, I’m good at ideas and finding something that is expressive and connects with other people.

“The things that communicate with other people are the things that resonate with me at the time of writing, and I have to always remind myself of that. The biggest mistake is to try to please everyone. If you mix all the colours together you’ll end up with a brown painting.”

—MJ Cole

You speak about making the music you “believe to be true.” What do you mean by this?

I’ve learned that sincerity is important in music. The most successful records I’ve made have been without thinking about anyone else. Like when I made “Sincere,” the single, that was in my bedroom at home in St. Margarets. It wasn’t made for anyone, and I didn’t even know it was going to be released. I had some things in front of me, like a palette, and I just started to paint. I didn’t even think about it. And that’s the same with this record really. It was an emotional outpouring. I didn’t have any pressures or constraints. It’s a direct communication of me as a musician, and I think the biggest purpose for me is to resonate with other people; to communicate with them on a musical and personal level.

So you weren’t trying to please the listener?

No, I was trying to make a record for me, and a record that other people would understand and resonate with. I certainly wasn’t thinking the listener is going to think or feel this; I really just followed my instincts and made the record that I felt was truest to myself.

Have you struggled to maintain this sincerity, as your audience has grown?

I’ve definitely had moments where I’ve looked at what everyone else is doing, and considered following them, but I’ve learned that that never works for me. The things that communicate with other people are the things that resonate with me at the time of writing, and I have to always remind myself of that. The biggest mistake is to try to please everyone. If you mix all the colours together you’ll end up with a brown painting. I’ve had some moderate success so it’s easier for me to trust myself.

Reflecting on the album, does it give you more satisfaction than making dance music?

It does, because there are no constraints. I am more proud of these pieces as pieces of art. They’re not so functional; it’s not like there’s got to be 16 bars at the beginning otherwise DJs aren’t going to play it. In dance music quite often, I find myself having to take a lot of stuff out or having to hold myself back from putting too much in, because over my decades of DJing I have been there in the booth when I’ve played something the day before and it has loads of strings and piano in, and it just mushes out. You don’t really hear anything. And something else that has just a kick, snare, a bass, and one synth sound will just sound much more direct. It was great to be able to indulge myself in all the stuff I’ve been trying to hold back before. Suddenly all that stuff was fair game and allowed.

Was it also a cathartic experience?

Certainly, because piano is my biggest means of expression. I’m not great at expressing emotions on a normal human level, but music seems to be my blowhole, to release myself. It’s the way I know best. When I play the piano, it’s my form of meditation; I don’t think about shopping lists or anything else. I just go into this kind of state, as if there’s another force that comes through me.

The album places you close to this neoclassical category of contemporary music. Is there somewhere you’d like to position yourself?

It’s funny because before we actually started making the album, I’d visit Tom Lewis, who is my A&R guy at Decca, and just sit in his office and listen to stuff. I didn’t really know anything about neoclassical at the time, and I didn’t know who Nils Frahm or Ólafur Arnalds were, or anything like that, and he introduced me to lots of people in that realm. I have a playlist here called “Decca Vibes” which documents all the things I was listening to in this period, like Johnnie Greenwood, Kiasmos, Jon Hopkins, Joni Mitchell, Ryuichi Sakamoto. I actually listened to it when I was writing the album.

Have you ever considered trying your hand at film scoring?

That’s something else I have my sights on. One hundred percent. I’ve always seen myself as going that way. I have this vision of going to a film premiere, where nobody knows who I am, and I just sit in a big, red velvety chair while my music is playing in a film. It’s like how I used to sneak into clubs when I first made garage records and the DJ would have a dubplate of something I’d made, and I’d just be there anonymously in the crowd. I’d get a real buzz from that.

All photos: Isaac Confino