WARNING: CHAINSAW MAN MANGA PART 2 SPOILERS

I recently read the book Quarterlife: The Search for Self in Early Adulthood by therapist Satya Doyle Byock, which talks about the concept of the “quarterlife crisis.” According to Doyle, it is when someone in early adulthood feels a sense of dissatisfaction from a certain imbalance—in the pursuit of either meaning or stability, the other is never developed. People typically tend toward one side, and if they fail to teach a degree of balance, it can eventually turn into a midlife crisis. While the book is primarily aimed towards actual flesh-and-blood people, that struggle between meaning and stability also made me think of the hero of a current popular manga: Denji from Chainsaw Man.

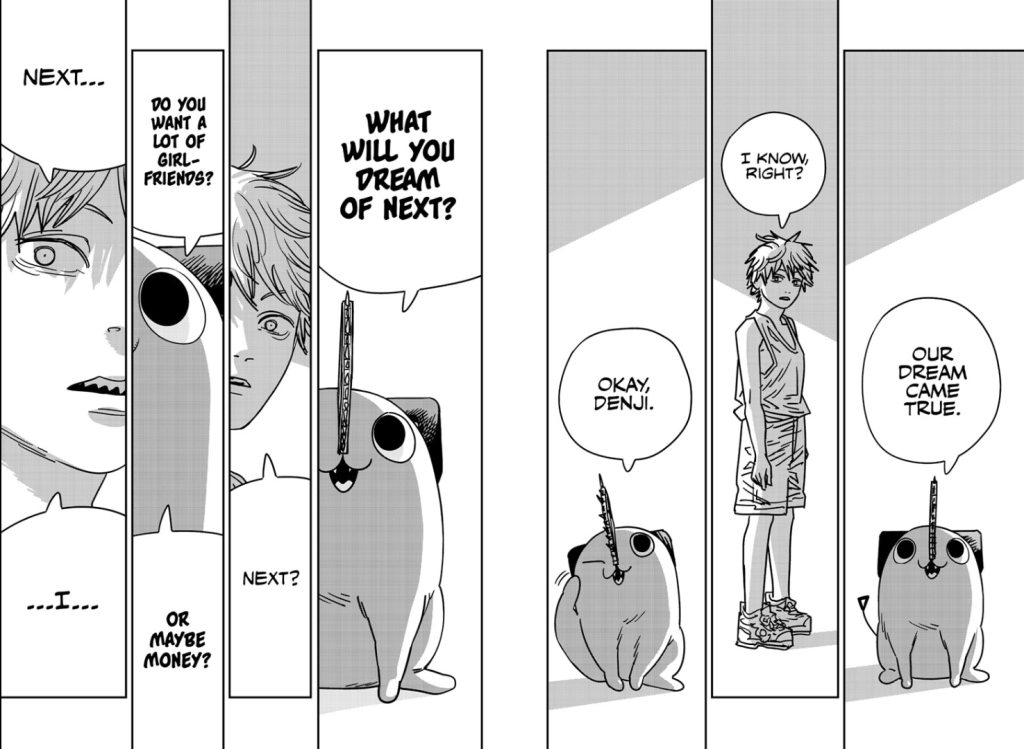

From the start, what we know of Denji is that he basically has nothing, and even his highest aspirations come from scarcity: He wants to eat jam on toast, and he wants to touch a boob. While he comes across as shallow and horny (and he is both), this is Denji seeking the stability he’s never had, symbolized in the freedom to eat whatever he wants and to be with a girl. Thanks to his Chainsaw Devil powers, he starts to get that life, but it’s also clear that things aren’t hitting quite right. “This isn’t what I expected it to be” is a common thought by Denji, as if all that stability brings him is a search for meaning.

However, when Denji pursues meaning, including embracing the public image of Chainsaw Man as a dark hero, he instead starts to wonder, “Is this really all there is?” The comfort of stability calls to him—a life where he doesn’t have to be Chainsaw Man anymore. Even as others try to force a sense of meaning onto Denji, he resists because he’s trying to see how he really feels.

This vacillating between stability and meaning occurs across Part 1 of the manga. It also extends into Part 2, where I find Denji’s to be even more intense. The addition of the character Nayuta shows a side of him we had only barely glimpsed before—now a big brother/dad of sorts, he tries to provide for her a comfortable life full of opportunities that he himself never had. My heart actually feels joy when I see Nayuta take after Denji’s odd mannerisms, or when she enthusiastically and aggressively participates in class. I suspect there might be an answer for him in their relationship.

Denji is not an “early adult,” but rather a teen. What he experiences is not that period in which society tells us that people are supposed to be in their prime. However, I do think Denji’s plight in this area is part of why Chainsaw Man has been such a phenomenon. The typical shounen hero does not have anything resembling a quarterlife crisis. They usually have an ambition that drives them, and is the presumed end goal of the story. The fact that Denji struggles as much as he does, on top of being both vapid and profound at once, is eminently relatable.

Of course, I highly doubt that the author Fujimoto has been thinking specifically of quarterlife crisis. Even if he was, there’s a good chance Denji just ends up in a worse place by the end. But I now see a painful and at times conflicting search for meaning and stability that is ever present in Chainsaw Man, and I think it gives the series a powerfully profound psychological quality absent in so many of its peers.